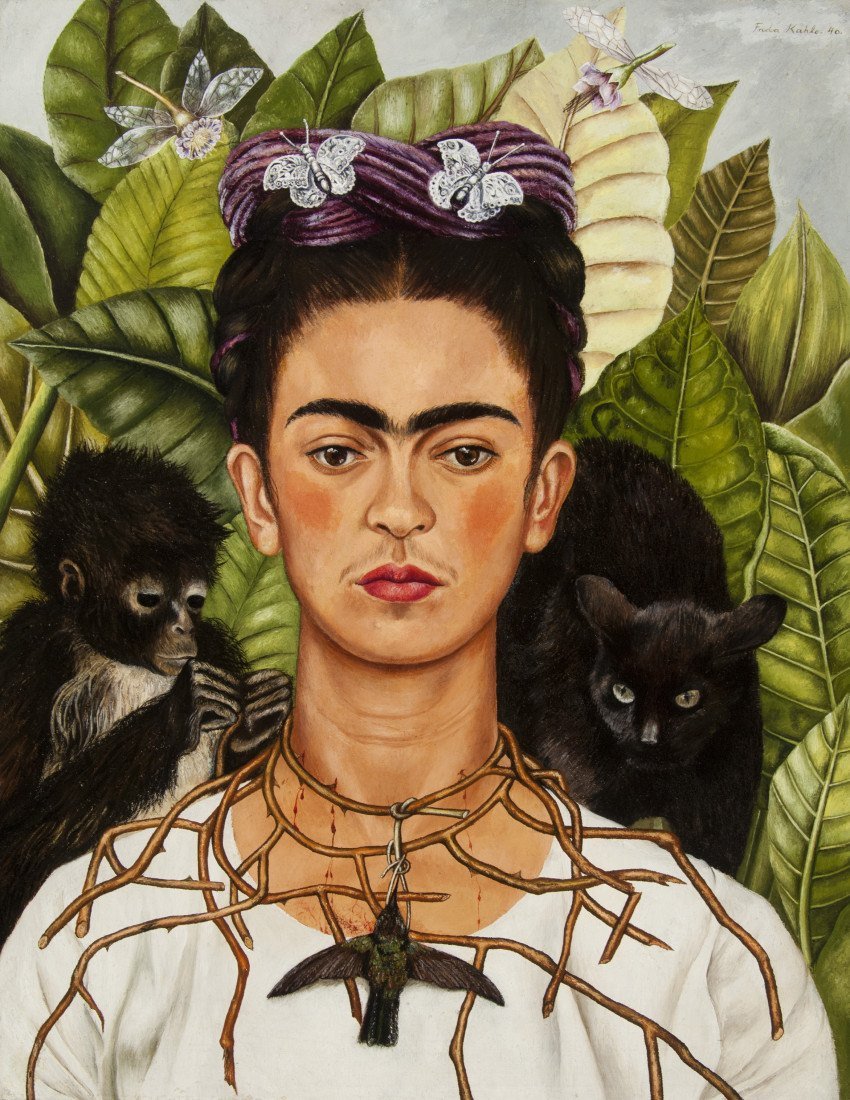

To celebrate National Hispanic Heritage Month, we focus on the painter, Frida Khalo. Frida Kahlo began to paint in 1925, while recovering from a near-fatal bus accident that devastated her body and marked the beginning of lifelong physical ordeals. Over the next three decades, she would produce a relatively small yet consistent and arresting body of work. In meticulously executed paintings, Kahlo portrayed herself again and again, simultaneously exploring, questioning, and staging her self and identity. She also often evoked fraught episodes from her life, including her ongoing struggle with physical pain and the emotional distress caused by her turbulent relationship with celebrated painter Diego Rivera.

Such personal subject matter, along with the intimate scale of her paintings, sharply contrasted with the work of her acclaimed contemporaries, the Mexican Muralists. Launched in the wake of the Mexican Revolution and backed by the government, the Mexican Muralist movement aimed to produce monumental public murals that mined the country’s national history and identity. An avowed Communist, like her peers Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, Kahlo at times expressed her desire to paint “something useful for the Communist revolutionary movement,” yet her art remained “very far from work that could serve the Party.”1 She nonetheless participated in her peers’ exaltation of Mexico’s indigenous culture, avidly collecting Mexican popular art and often making use of its motifs and techniques. In My Grandparents, My Parents, and I, for example, she adopted the format of retablos, small devotional paintings made on metallic plates. She also carefully crafted a flamboyant Mexican persona for herself, wearing colorful folk dresses and pre-Columbian jewelry, in a performative display of her identity.

Kahlo’s early recognition was prompted by French poet and founder of Surrealism André Breton, who enthusiastically embraced her art as self-made Surrealism, and included her work in his 1940 International Exhibition of Surrealism in Mexico City. Yet if her art had an uncanny quality akin to the movement’s tenets, Kahlo resisted the association: “They thought I was a Surrealist but I wasn’t,” she said. “I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.”2